Moving Forward While Looking Back: The First 19 Months of John Byrne’s Fantastic Four

Fantastic Four #232-250

John Byrne

Recently, I’ve been rereading John Byrne’s long and lauded run on the first volume of Fantastic Four. I’ve read through these issues several times in the past, and indeed this run of comic books holds special significance for me in that my first encounter with them marked the first time I became distinctly aware of the creator of the comic books, rather than just the characters. After reading these comics, John Byrne was the first artist whose work I sought out based on his talents, rather than my interest in the characters he was working on. In short, I went in a Fantastic Four fan, and came out a John Byrne fan.

Recently, I’ve been rereading John Byrne’s long and lauded run on the first volume of Fantastic Four. I’ve read through these issues several times in the past, and indeed this run of comic books holds special significance for me in that my first encounter with them marked the first time I became distinctly aware of the creator of the comic books, rather than just the characters. After reading these comics, John Byrne was the first artist whose work I sought out based on his talents, rather than my interest in the characters he was working on. In short, I went in a Fantastic Four fan, and came out a John Byrne fan.

As many times as I’ve read a lot of this material, I’ve not read the run in its entirety from the first to the final issue, and indeed there are a couple of issues I acquired only recently I’ve not read at all. I thought, then, that my thoughts on this rereading might make for an interesting blog post, or even series of posts. Certainly, my fondness for John Byrne, both as an artist and as a man, has fallen considerably since I first dubbed him my “favorite artist” years ago, and the comics under consideration here are hardly flawless, but for the most part I’m delighted by how much I’m enjoying reading through these old comics, generally finding that they hold up quite well as a series of solidly crafted superhero comics that, so far at least, improve in quality as the series progresses.

Byrne’s first issue of Fantastic Four is titled “Back to Basics!” That title, and the issue itself, provide a perfect example of Byrne’s basic approach to the series. I’m afraid I’ve read very little of the vast stretch of issues that is the post-Lee/Kirby, pre-Byrne Fantastic Four, but it’s clear Byrne feels the book had wandered pretty far off the mark, as his approach is aggressively conservative, concerned, at least in these initial issues, not so much with forging a new path as with bringing the characters and concept, well….back to basics. In this first issue, Diablo, a B-list villain from the F.F.’s rogues gallery, creates four creatures, each of whom embodies one of the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire) and sends them to attack the Fantastic Four. It has often been observed that the powers of the Fantastic Four mirror these four elemental properties (the Thing is earth, the Invisible Girl is air, Mr. Fantastic is water, and the Human Torch is fire), and Diablo’s plan is to have each of the elemental creatures attack a member of the team whose power is not analogous to the creature’s own. So, the earth creature attacks the Invisible Girl rather than the Thing, the Human Torch battles the air creature instead of the fire elemental, and so forth. Eventually, Mr. Fantastic deduces the nature of Diablo’s scheme, as well as coming up with a way to defeat the creatures: They are destroyed when the state of the matter of which they are constructed changes, and so some clever methods are devised to do just that, and the issue wraps up with a cameo appearance by Dr. Strange, who assists the F.F. in tracking down and capturing Diablo.

Byrne’s first issue of Fantastic Four is titled “Back to Basics!” That title, and the issue itself, provide a perfect example of Byrne’s basic approach to the series. I’m afraid I’ve read very little of the vast stretch of issues that is the post-Lee/Kirby, pre-Byrne Fantastic Four, but it’s clear Byrne feels the book had wandered pretty far off the mark, as his approach is aggressively conservative, concerned, at least in these initial issues, not so much with forging a new path as with bringing the characters and concept, well….back to basics. In this first issue, Diablo, a B-list villain from the F.F.’s rogues gallery, creates four creatures, each of whom embodies one of the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire) and sends them to attack the Fantastic Four. It has often been observed that the powers of the Fantastic Four mirror these four elemental properties (the Thing is earth, the Invisible Girl is air, Mr. Fantastic is water, and the Human Torch is fire), and Diablo’s plan is to have each of the elemental creatures attack a member of the team whose power is not analogous to the creature’s own. So, the earth creature attacks the Invisible Girl rather than the Thing, the Human Torch battles the air creature instead of the fire elemental, and so forth. Eventually, Mr. Fantastic deduces the nature of Diablo’s scheme, as well as coming up with a way to defeat the creatures: They are destroyed when the state of the matter of which they are constructed changes, and so some clever methods are devised to do just that, and the issue wraps up with a cameo appearance by Dr. Strange, who assists the F.F. in tracking down and capturing Diablo.

In many ways, this first issue serves as a kind of template for much of what will follow. For one thing, it is entirely self-contained, a single short story with a beginning, middle, and end. While there are a few two- and three- part tales in the group of issues I’m looking at here, for the most part the stories are, like this one, self-contained. The structure of this issue also provides Byrne a nice showcase for his take on the various members of the team. While he will leave his mark most noticeably on the Invisible Girl (she uses her power in a new, now familiar, way for the first time in this issue), my favorite character under Byrne’s stewardship is Reed Richards, Mr. Fantastic. In character and in physical appearance, Reed is the prototypical absent-minded professor. Many of these stories involve a kind of mystery that Reed must solve in order to save the day, with the other members of the team functioning as extensions of Reed’s plan, indeed as extensions of his vision of the team and it’s mission. I love the way Byrne draws him, too. He is quite thin, fit but certainly not brawny as he was depicted even in the later Kirby issues, with a slightly large forehead, evoking both his intelligence and age relative to his teammates. Johnny is the hunky, faux-bad-boy who would probably be a nerd were he not so physically attractive, and the Thing is the Thing.

A couple of unfortunate clunkers follow this promising first issue. First is a solo Human Torch story in which he does some uncharacteristic detective work to try and solve a years-old crime at the request of an old acquaintance. Like the first issue, it’s a well-executed short story, but not particularly interesting or thrilling, and a bit of a disappointment in that it focuses only on one member of the foursome, which seems somewhat inappropriate so early in Byrne’s run. Following this is “The Man with the Power!,” a one-off about an ordinary Joe who, unbeknownst to him, has the power to alter reality itself. Far from the most original concept in genre fiction, and nothing particularly interesting or innovative is done with it here. Byrne seems to be keeping the Fantastic Four themselves at something of a distance in these two issues, utilizing them more as devices in the tightly-constructed plots he has devised rather than developing the story outward from the characters, and this works to the book’s detriment. Subsequent issues will see a subtle, welcome shift towards richer characterization and more time spent with our main cast.

A couple of unfortunate clunkers follow this promising first issue. First is a solo Human Torch story in which he does some uncharacteristic detective work to try and solve a years-old crime at the request of an old acquaintance. Like the first issue, it’s a well-executed short story, but not particularly interesting or thrilling, and a bit of a disappointment in that it focuses only on one member of the foursome, which seems somewhat inappropriate so early in Byrne’s run. Following this is “The Man with the Power!,” a one-off about an ordinary Joe who, unbeknownst to him, has the power to alter reality itself. Far from the most original concept in genre fiction, and nothing particularly interesting or innovative is done with it here. Byrne seems to be keeping the Fantastic Four themselves at something of a distance in these two issues, utilizing them more as devices in the tightly-constructed plots he has devised rather than developing the story outward from the characters, and this works to the book’s detriment. Subsequent issues will see a subtle, welcome shift towards richer characterization and more time spent with our main cast.

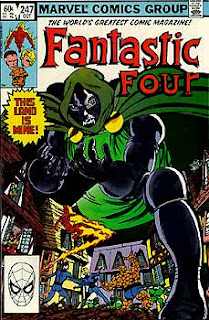

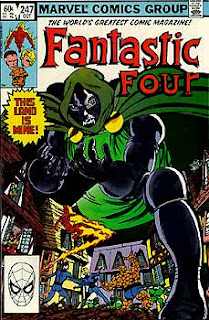

After a battle in space with Ego, the Living Planet, the F.F. return to Earth for what is possibly the most acclaimed single issue in this run of comics, #236’s extra-sized epic, “Terror in a Tiny Town.” In this story, the Fantastic Four’s memories have been altered, and their minds have been placed inside tiny robot duplicates of themselves, who inhabit a miniaturized town called “Liddleville,” completely unaware that they were ever the Fantastic Four. Their life in Liddleville is an idealized one, with Reed Richards working as a professor at a local college, Sue as his adoring housewife, and, most significantly, a very human Ben Grimm married to Alicia Masters, who is not, as she usually is, blind. Dr. Doom and the Puppet Master are the ones behind the scheme, and both of them are able to enter tiny robot duplicates in the town as well, the Puppet Master as himself, Alicia’s stepfather Philip Masters, and Doom as “Professor Vaughan,” a colleague of Reed’s at the college who continually berates Dr. Richards for his stupidity and ineptitude, just for the fun of it. Doom’s a bit of an ass, you see. Eventually, Reed figures the whole thing out, the F.F. are returned to their original bodies, and Doom and the Puppet Master are trapped inside Liddleville. While I don’t know that this story is quite as good as its reputation suggests, I did quite enjoy revisiting it. Byrne makes the smart choice of beginning the story after the F.F. have already been placed in the trap, so the reader has no idea what is actually going on, until slowly the truth of the predicament is revealed. It’s a nice idea for a “special” issue, too (#236 marks the twentieth anniversary of the Fantastic Four), as the Fantastic Four must now choose to play the roles fate forced them into years ago, rather than remain in the gilded cage they’ve found themselves in. The tragedy of the Thing is of course played for optimal melodrama here. With all it has going for it, there are some distractingly goofy elements that keep it from being a great Fantastic Four story, particularly some of the logistics of Doom’s and the Puppet Master’s plan. The Fantastic Four are able to regain their powers by subjecting their tiny robot selves to a “lesalle-devaney particle accelerator” which has been constructed in miniature in the laboratory in which Reed works. Why did Doom go to what must have been extraordinary lengths to construct a device he must have known was capable of giving the Fantastic Four their powers back? Well, because “the knowledge that so delicious a mechanism as the accelerator is available, but denied to him will drive Richards into ever greater depths of despair and confusion,” of course. I told you Doom was an ass. Oh, and he couldn’t have just built a fake device because “Doom couldn’t risk my recognizing a fake, even in my befuddled state!” Right.

Liddleville is an idealized one, with Reed Richards working as a professor at a local college, Sue as his adoring housewife, and, most significantly, a very human Ben Grimm married to Alicia Masters, who is not, as she usually is, blind. Dr. Doom and the Puppet Master are the ones behind the scheme, and both of them are able to enter tiny robot duplicates in the town as well, the Puppet Master as himself, Alicia’s stepfather Philip Masters, and Doom as “Professor Vaughan,” a colleague of Reed’s at the college who continually berates Dr. Richards for his stupidity and ineptitude, just for the fun of it. Doom’s a bit of an ass, you see. Eventually, Reed figures the whole thing out, the F.F. are returned to their original bodies, and Doom and the Puppet Master are trapped inside Liddleville. While I don’t know that this story is quite as good as its reputation suggests, I did quite enjoy revisiting it. Byrne makes the smart choice of beginning the story after the F.F. have already been placed in the trap, so the reader has no idea what is actually going on, until slowly the truth of the predicament is revealed. It’s a nice idea for a “special” issue, too (#236 marks the twentieth anniversary of the Fantastic Four), as the Fantastic Four must now choose to play the roles fate forced them into years ago, rather than remain in the gilded cage they’ve found themselves in. The tragedy of the Thing is of course played for optimal melodrama here. With all it has going for it, there are some distractingly goofy elements that keep it from being a great Fantastic Four story, particularly some of the logistics of Doom’s and the Puppet Master’s plan. The Fantastic Four are able to regain their powers by subjecting their tiny robot selves to a “lesalle-devaney particle accelerator” which has been constructed in miniature in the laboratory in which Reed works. Why did Doom go to what must have been extraordinary lengths to construct a device he must have known was capable of giving the Fantastic Four their powers back? Well, because “the knowledge that so delicious a mechanism as the accelerator is available, but denied to him will drive Richards into ever greater depths of despair and confusion,” of course. I told you Doom was an ass. Oh, and he couldn’t have just built a fake device because “Doom couldn’t risk my recognizing a fake, even in my befuddled state!” Right.

Byrne’s next significant contribution to the series comes a couple of issues later, with the revelation of the secret of Frankie Raye. Frankie is Johnny Storm’s sort-of girlfriend when Byrne begins his run on the series, a cute redhead who, despite her attraction to the Torch, seems repulsed by his flaming power. Byrne had been dropping subtle hints as to Frankie’s dark secret throughout the initial issues of his run, and it all comes to a head in #238, when it is revealed that Frankie is actually the daughter of the scientist who created the original Human Torch. It seems she was accidentally exposed to some of her father’s chemicals years ago, and developed flaming powers of her own. In a fit of what can only be described as extreme overreaction, her father hypnotized Frankie so that she would forget the incident, and indeed her entire past, and live her life without knowledge of her own superpowers. The scheme works until she meets Johnny, at which point the mental blocks placed in her mind begin to break down via exposure to this new Human Torch, until Frankie finally “flames on” herself, becoming, in effect, a second, female Human Torch. I like Frankie, particularly her design. When using her powers, Frankie’s skin appears bright red, but without those little lines that are drawn over the Human Torch. Her hair appears as billowing yellow and orange fire, and her costume is essentially a one-piece yellow bathing suit which melts to flame around the edges. A great, dynamic looking design, but one that was destined not to be around very long.

Byrne’s next significant contribution to the series comes a couple of issues later, with the revelation of the secret of Frankie Raye. Frankie is Johnny Storm’s sort-of girlfriend when Byrne begins his run on the series, a cute redhead who, despite her attraction to the Torch, seems repulsed by his flaming power. Byrne had been dropping subtle hints as to Frankie’s dark secret throughout the initial issues of his run, and it all comes to a head in #238, when it is revealed that Frankie is actually the daughter of the scientist who created the original Human Torch. It seems she was accidentally exposed to some of her father’s chemicals years ago, and developed flaming powers of her own. In a fit of what can only be described as extreme overreaction, her father hypnotized Frankie so that she would forget the incident, and indeed her entire past, and live her life without knowledge of her own superpowers. The scheme works until she meets Johnny, at which point the mental blocks placed in her mind begin to break down via exposure to this new Human Torch, until Frankie finally “flames on” herself, becoming, in effect, a second, female Human Torch. I like Frankie, particularly her design. When using her powers, Frankie’s skin appears bright red, but without those little lines that are drawn over the Human Torch. Her hair appears as billowing yellow and orange fire, and her costume is essentially a one-piece yellow bathing suit which melts to flame around the edges. A great, dynamic looking design, but one that was destined not to be around very long.

You see, Frankie didn’t get to enjoy her status as a second Human Torch and almost-fifth member of the F.F. for very long. During her brief career as a superhero, Frankie seemed unnaturally addicted to her power, with an insatiable lust for adventure and a seeming willingness to break the F.F.’s “no killing our enemies” rule. Yes, bad things were brewing for poor, troubled Frankie, and it would all culminate in my personal favorite story-arc of Byrne’s run, his own “Galactus Trilogy” in issues #242-244. Galactus has once again returned to earth, in pursuit of his rebellious herald, Terrax. Over the course of these issues, Terrax is depowered by Galactus after a failed attempt to recruit the Fantastic Four into offing the big guy in order to free Terrax from his bondage. When all is said and done, Galactus needs a new herald, and our own Frankie Raye shockingly volunteers to take up the position once held by the Silver Surfer. After a quick “power-up” from Galactus resulting in a new, sleeker look, Frankie flies off into the cosmos, leaving her life on earth, and a very heartbroken Human Torch, behind forever. It’s a pretty neat little three-parter, featuring, at one point, the Fantastic Four fighting alongside Dr. Strange and several of the Avengers to battle the devourer of worlds.

You see, Frankie didn’t get to enjoy her status as a second Human Torch and almost-fifth member of the F.F. for very long. During her brief career as a superhero, Frankie seemed unnaturally addicted to her power, with an insatiable lust for adventure and a seeming willingness to break the F.F.’s “no killing our enemies” rule. Yes, bad things were brewing for poor, troubled Frankie, and it would all culminate in my personal favorite story-arc of Byrne’s run, his own “Galactus Trilogy” in issues #242-244. Galactus has once again returned to earth, in pursuit of his rebellious herald, Terrax. Over the course of these issues, Terrax is depowered by Galactus after a failed attempt to recruit the Fantastic Four into offing the big guy in order to free Terrax from his bondage. When all is said and done, Galactus needs a new herald, and our own Frankie Raye shockingly volunteers to take up the position once held by the Silver Surfer. After a quick “power-up” from Galactus resulting in a new, sleeker look, Frankie flies off into the cosmos, leaving her life on earth, and a very heartbroken Human Torch, behind forever. It’s a pretty neat little three-parter, featuring, at one point, the Fantastic Four fighting alongside Dr. Strange and several of the Avengers to battle the devourer of worlds.

Following this is a weird Invisible Girl solo issue where Sue’s and Reed’s young son Franklin turns himself into an adult, a two-part story featuring the return of Dr. Doom and his restoration as Latveria’s monarch, an issue featuring the Inhumans, and finally a two-part story culminating in the extra-sized 250th issue, wherein the Fantastic Four get their asses kicked by the Superman-like Gladiator before recovering to help him defeat a quartet of Skrulls disguised as the Uncanny X-Men.

So, we’re off to a good start for quite an entertaining run of comic books. As I said, I’ve really been enjoying revisiting these issues, and have found much to appreciate. Although it’s not fashionable these days to say so, I really enjoy John Byrne’s artwork. I’ve discussed his designs of Mr. Fantastic and Frankie Raye, but all of the characters look terrific. His Thing is perfect, in both physical appearance and characterization. The dopey melodrama the character finds himself caught up in works most of the time because Ben Grimm is, at heart, a dopey, melodramatic guy. I like him.

While I certainly recommend these issues to anyone who enjoys good superhero comic books, it must also be said that they fall far short of the brilliance that was Jack Kirby’s take on these extraordinary characters he co-created with Stan Lee. Certainly, Lee’s dialogue was incredibly goofy and melodramatic, but it did have a certain flow and cadence that worked well in collaboration with Kirby’s powerful artwork. Byrne’s dialogue, by contrast, can be quite awkward, particularly when he is conveying clumsy, complex exposition through his characters, which he does often, despite the fact that he also employs copious, at times overwritten, narrative captions. While it is probably unfair to compare any artist who works on these characters (or any superhero comic book) to Jack Kirby, I’m mostly disappointed that Byrne is, at times, too reverent towards the source material. While his “back to basics” approach was probably refreshing for a lot of fans who had been subjected for years to a Fantastic Four that had become just another superhero comic book, I think it would have been nice if Byrne had brought more to the table creatively, in regards to the creation of new heroes and villains, and the exploration of new worlds and universes. Such an approach is a big part of what made Kirby’s take on the characters so great, and would have been more in keeping with the spirit of Kirby than simply utilizing the elements that had already been introduced in the series. At times, Byrne comes across here not so much as an artist with a bold new vision for the future of these characters, as he does a museum curator who is eager to show off the work of a master whose collection he has been lucky enough to have been granted association with.

While I certainly recommend these issues to anyone who enjoys good superhero comic books, it must also be said that they fall far short of the brilliance that was Jack Kirby’s take on these extraordinary characters he co-created with Stan Lee. Certainly, Lee’s dialogue was incredibly goofy and melodramatic, but it did have a certain flow and cadence that worked well in collaboration with Kirby’s powerful artwork. Byrne’s dialogue, by contrast, can be quite awkward, particularly when he is conveying clumsy, complex exposition through his characters, which he does often, despite the fact that he also employs copious, at times overwritten, narrative captions. While it is probably unfair to compare any artist who works on these characters (or any superhero comic book) to Jack Kirby, I’m mostly disappointed that Byrne is, at times, too reverent towards the source material. While his “back to basics” approach was probably refreshing for a lot of fans who had been subjected for years to a Fantastic Four that had become just another superhero comic book, I think it would have been nice if Byrne had brought more to the table creatively, in regards to the creation of new heroes and villains, and the exploration of new worlds and universes. Such an approach is a big part of what made Kirby’s take on the characters so great, and would have been more in keeping with the spirit of Kirby than simply utilizing the elements that had already been introduced in the series. At times, Byrne comes across here not so much as an artist with a bold new vision for the future of these characters, as he does a museum curator who is eager to show off the work of a master whose collection he has been lucky enough to have been granted association with.

Still, if memory serves, future issues in this run will see Byrne building on the foundation he’s established here, even going so far as to replace one of the original team with another character. Also, while flaws should not be overlooked, the strength of these comics should not be understated: Byrne proves himself in these issues to be a man firmly in command of his craft, with an impressive ability to construct satisfying short adventure stories that satisfy as individual, 20-page units, but also add up to an engaging serial narrative. His character designs are first-rate, and his grasp of the characters and their personalities is very strong. Were these comics being released today, they would be amongst the best currently being offered by the superhero publishers, and if that comes across as damnation by faint praise, it was not intended as such. While these comic books may not quite deserve a place next to Kirby’s run in the canon of great superhero comics, they certainly deserve to be read and enjoyed on their own merits, and I hope that this essay has gone some small way in encouraging you to do so.

John Byrne

Recently, I’ve been rereading John Byrne’s long and lauded run on the first volume of Fantastic Four. I’ve read through these issues several times in the past, and indeed this run of comic books holds special significance for me in that my first encounter with them marked the first time I became distinctly aware of the creator of the comic books, rather than just the characters. After reading these comics, John Byrne was the first artist whose work I sought out based on his talents, rather than my interest in the characters he was working on. In short, I went in a Fantastic Four fan, and came out a John Byrne fan.

Recently, I’ve been rereading John Byrne’s long and lauded run on the first volume of Fantastic Four. I’ve read through these issues several times in the past, and indeed this run of comic books holds special significance for me in that my first encounter with them marked the first time I became distinctly aware of the creator of the comic books, rather than just the characters. After reading these comics, John Byrne was the first artist whose work I sought out based on his talents, rather than my interest in the characters he was working on. In short, I went in a Fantastic Four fan, and came out a John Byrne fan. As many times as I’ve read a lot of this material, I’ve not read the run in its entirety from the first to the final issue, and indeed there are a couple of issues I acquired only recently I’ve not read at all. I thought, then, that my thoughts on this rereading might make for an interesting blog post, or even series of posts. Certainly, my fondness for John Byrne, both as an artist and as a man, has fallen considerably since I first dubbed him my “favorite artist” years ago, and the comics under consideration here are hardly flawless, but for the most part I’m delighted by how much I’m enjoying reading through these old comics, generally finding that they hold up quite well as a series of solidly crafted superhero comics that, so far at least, improve in quality as the series progresses.

Byrne’s first issue of Fantastic Four is titled “Back to Basics!” That title, and the issue itself, provide a perfect example of Byrne’s basic approach to the series. I’m afraid I’ve read very little of the vast stretch of issues that is the post-Lee/Kirby, pre-Byrne Fantastic Four, but it’s clear Byrne feels the book had wandered pretty far off the mark, as his approach is aggressively conservative, concerned, at least in these initial issues, not so much with forging a new path as with bringing the characters and concept, well….back to basics. In this first issue, Diablo, a B-list villain from the F.F.’s rogues gallery, creates four creatures, each of whom embodies one of the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire) and sends them to attack the Fantastic Four. It has often been observed that the powers of the Fantastic Four mirror these four elemental properties (the Thing is earth, the Invisible Girl is air, Mr. Fantastic is water, and the Human Torch is fire), and Diablo’s plan is to have each of the elemental creatures attack a member of the team whose power is not analogous to the creature’s own. So, the earth creature attacks the Invisible Girl rather than the Thing, the Human Torch battles the air creature instead of the fire elemental, and so forth. Eventually, Mr. Fantastic deduces the nature of Diablo’s scheme, as well as coming up with a way to defeat the creatures: They are destroyed when the state of the matter of which they are constructed changes, and so some clever methods are devised to do just that, and the issue wraps up with a cameo appearance by Dr. Strange, who assists the F.F. in tracking down and capturing Diablo.

Byrne’s first issue of Fantastic Four is titled “Back to Basics!” That title, and the issue itself, provide a perfect example of Byrne’s basic approach to the series. I’m afraid I’ve read very little of the vast stretch of issues that is the post-Lee/Kirby, pre-Byrne Fantastic Four, but it’s clear Byrne feels the book had wandered pretty far off the mark, as his approach is aggressively conservative, concerned, at least in these initial issues, not so much with forging a new path as with bringing the characters and concept, well….back to basics. In this first issue, Diablo, a B-list villain from the F.F.’s rogues gallery, creates four creatures, each of whom embodies one of the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire) and sends them to attack the Fantastic Four. It has often been observed that the powers of the Fantastic Four mirror these four elemental properties (the Thing is earth, the Invisible Girl is air, Mr. Fantastic is water, and the Human Torch is fire), and Diablo’s plan is to have each of the elemental creatures attack a member of the team whose power is not analogous to the creature’s own. So, the earth creature attacks the Invisible Girl rather than the Thing, the Human Torch battles the air creature instead of the fire elemental, and so forth. Eventually, Mr. Fantastic deduces the nature of Diablo’s scheme, as well as coming up with a way to defeat the creatures: They are destroyed when the state of the matter of which they are constructed changes, and so some clever methods are devised to do just that, and the issue wraps up with a cameo appearance by Dr. Strange, who assists the F.F. in tracking down and capturing Diablo. In many ways, this first issue serves as a kind of template for much of what will follow. For one thing, it is entirely self-contained, a single short story with a beginning, middle, and end. While there are a few two- and three- part tales in the group of issues I’m looking at here, for the most part the stories are, like this one, self-contained. The structure of this issue also provides Byrne a nice showcase for his take on the various members of the team. While he will leave his mark most noticeably on the Invisible Girl (she uses her power in a new, now familiar, way for the first time in this issue), my favorite character under Byrne’s stewardship is Reed Richards, Mr. Fantastic. In character and in physical appearance, Reed is the prototypical absent-minded professor. Many of these stories involve a kind of mystery that Reed must solve in order to save the day, with the other members of the team functioning as extensions of Reed’s plan, indeed as extensions of his vision of the team and it’s mission. I love the way Byrne draws him, too. He is quite thin, fit but certainly not brawny as he was depicted even in the later Kirby issues, with a slightly large forehead, evoking both his intelligence and age relative to his teammates. Johnny is the hunky, faux-bad-boy who would probably be a nerd were he not so physically attractive, and the Thing is the Thing.

A couple of unfortunate clunkers follow this promising first issue. First is a solo Human Torch story in which he does some uncharacteristic detective work to try and solve a years-old crime at the request of an old acquaintance. Like the first issue, it’s a well-executed short story, but not particularly interesting or thrilling, and a bit of a disappointment in that it focuses only on one member of the foursome, which seems somewhat inappropriate so early in Byrne’s run. Following this is “The Man with the Power!,” a one-off about an ordinary Joe who, unbeknownst to him, has the power to alter reality itself. Far from the most original concept in genre fiction, and nothing particularly interesting or innovative is done with it here. Byrne seems to be keeping the Fantastic Four themselves at something of a distance in these two issues, utilizing them more as devices in the tightly-constructed plots he has devised rather than developing the story outward from the characters, and this works to the book’s detriment. Subsequent issues will see a subtle, welcome shift towards richer characterization and more time spent with our main cast.

A couple of unfortunate clunkers follow this promising first issue. First is a solo Human Torch story in which he does some uncharacteristic detective work to try and solve a years-old crime at the request of an old acquaintance. Like the first issue, it’s a well-executed short story, but not particularly interesting or thrilling, and a bit of a disappointment in that it focuses only on one member of the foursome, which seems somewhat inappropriate so early in Byrne’s run. Following this is “The Man with the Power!,” a one-off about an ordinary Joe who, unbeknownst to him, has the power to alter reality itself. Far from the most original concept in genre fiction, and nothing particularly interesting or innovative is done with it here. Byrne seems to be keeping the Fantastic Four themselves at something of a distance in these two issues, utilizing them more as devices in the tightly-constructed plots he has devised rather than developing the story outward from the characters, and this works to the book’s detriment. Subsequent issues will see a subtle, welcome shift towards richer characterization and more time spent with our main cast. After a battle in space with Ego, the Living Planet, the F.F. return to Earth for what is possibly the most acclaimed single issue in this run of comics, #236’s extra-sized epic, “Terror in a Tiny Town.” In this story, the Fantastic Four’s memories have been altered, and their minds have been placed inside tiny robot duplicates of themselves, who inhabit a miniaturized town called “Liddleville,” completely unaware that they were ever the Fantastic Four. Their life in

Liddleville is an idealized one, with Reed Richards working as a professor at a local college, Sue as his adoring housewife, and, most significantly, a very human Ben Grimm married to Alicia Masters, who is not, as she usually is, blind. Dr. Doom and the Puppet Master are the ones behind the scheme, and both of them are able to enter tiny robot duplicates in the town as well, the Puppet Master as himself, Alicia’s stepfather Philip Masters, and Doom as “Professor Vaughan,” a colleague of Reed’s at the college who continually berates Dr. Richards for his stupidity and ineptitude, just for the fun of it. Doom’s a bit of an ass, you see. Eventually, Reed figures the whole thing out, the F.F. are returned to their original bodies, and Doom and the Puppet Master are trapped inside Liddleville. While I don’t know that this story is quite as good as its reputation suggests, I did quite enjoy revisiting it. Byrne makes the smart choice of beginning the story after the F.F. have already been placed in the trap, so the reader has no idea what is actually going on, until slowly the truth of the predicament is revealed. It’s a nice idea for a “special” issue, too (#236 marks the twentieth anniversary of the Fantastic Four), as the Fantastic Four must now choose to play the roles fate forced them into years ago, rather than remain in the gilded cage they’ve found themselves in. The tragedy of the Thing is of course played for optimal melodrama here. With all it has going for it, there are some distractingly goofy elements that keep it from being a great Fantastic Four story, particularly some of the logistics of Doom’s and the Puppet Master’s plan. The Fantastic Four are able to regain their powers by subjecting their tiny robot selves to a “lesalle-devaney particle accelerator” which has been constructed in miniature in the laboratory in which Reed works. Why did Doom go to what must have been extraordinary lengths to construct a device he must have known was capable of giving the Fantastic Four their powers back? Well, because “the knowledge that so delicious a mechanism as the accelerator is available, but denied to him will drive Richards into ever greater depths of despair and confusion,” of course. I told you Doom was an ass. Oh, and he couldn’t have just built a fake device because “Doom couldn’t risk my recognizing a fake, even in my befuddled state!” Right.

Liddleville is an idealized one, with Reed Richards working as a professor at a local college, Sue as his adoring housewife, and, most significantly, a very human Ben Grimm married to Alicia Masters, who is not, as she usually is, blind. Dr. Doom and the Puppet Master are the ones behind the scheme, and both of them are able to enter tiny robot duplicates in the town as well, the Puppet Master as himself, Alicia’s stepfather Philip Masters, and Doom as “Professor Vaughan,” a colleague of Reed’s at the college who continually berates Dr. Richards for his stupidity and ineptitude, just for the fun of it. Doom’s a bit of an ass, you see. Eventually, Reed figures the whole thing out, the F.F. are returned to their original bodies, and Doom and the Puppet Master are trapped inside Liddleville. While I don’t know that this story is quite as good as its reputation suggests, I did quite enjoy revisiting it. Byrne makes the smart choice of beginning the story after the F.F. have already been placed in the trap, so the reader has no idea what is actually going on, until slowly the truth of the predicament is revealed. It’s a nice idea for a “special” issue, too (#236 marks the twentieth anniversary of the Fantastic Four), as the Fantastic Four must now choose to play the roles fate forced them into years ago, rather than remain in the gilded cage they’ve found themselves in. The tragedy of the Thing is of course played for optimal melodrama here. With all it has going for it, there are some distractingly goofy elements that keep it from being a great Fantastic Four story, particularly some of the logistics of Doom’s and the Puppet Master’s plan. The Fantastic Four are able to regain their powers by subjecting their tiny robot selves to a “lesalle-devaney particle accelerator” which has been constructed in miniature in the laboratory in which Reed works. Why did Doom go to what must have been extraordinary lengths to construct a device he must have known was capable of giving the Fantastic Four their powers back? Well, because “the knowledge that so delicious a mechanism as the accelerator is available, but denied to him will drive Richards into ever greater depths of despair and confusion,” of course. I told you Doom was an ass. Oh, and he couldn’t have just built a fake device because “Doom couldn’t risk my recognizing a fake, even in my befuddled state!” Right.  Byrne’s next significant contribution to the series comes a couple of issues later, with the revelation of the secret of Frankie Raye. Frankie is Johnny Storm’s sort-of girlfriend when Byrne begins his run on the series, a cute redhead who, despite her attraction to the Torch, seems repulsed by his flaming power. Byrne had been dropping subtle hints as to Frankie’s dark secret throughout the initial issues of his run, and it all comes to a head in #238, when it is revealed that Frankie is actually the daughter of the scientist who created the original Human Torch. It seems she was accidentally exposed to some of her father’s chemicals years ago, and developed flaming powers of her own. In a fit of what can only be described as extreme overreaction, her father hypnotized Frankie so that she would forget the incident, and indeed her entire past, and live her life without knowledge of her own superpowers. The scheme works until she meets Johnny, at which point the mental blocks placed in her mind begin to break down via exposure to this new Human Torch, until Frankie finally “flames on” herself, becoming, in effect, a second, female Human Torch. I like Frankie, particularly her design. When using her powers, Frankie’s skin appears bright red, but without those little lines that are drawn over the Human Torch. Her hair appears as billowing yellow and orange fire, and her costume is essentially a one-piece yellow bathing suit which melts to flame around the edges. A great, dynamic looking design, but one that was destined not to be around very long.

Byrne’s next significant contribution to the series comes a couple of issues later, with the revelation of the secret of Frankie Raye. Frankie is Johnny Storm’s sort-of girlfriend when Byrne begins his run on the series, a cute redhead who, despite her attraction to the Torch, seems repulsed by his flaming power. Byrne had been dropping subtle hints as to Frankie’s dark secret throughout the initial issues of his run, and it all comes to a head in #238, when it is revealed that Frankie is actually the daughter of the scientist who created the original Human Torch. It seems she was accidentally exposed to some of her father’s chemicals years ago, and developed flaming powers of her own. In a fit of what can only be described as extreme overreaction, her father hypnotized Frankie so that she would forget the incident, and indeed her entire past, and live her life without knowledge of her own superpowers. The scheme works until she meets Johnny, at which point the mental blocks placed in her mind begin to break down via exposure to this new Human Torch, until Frankie finally “flames on” herself, becoming, in effect, a second, female Human Torch. I like Frankie, particularly her design. When using her powers, Frankie’s skin appears bright red, but without those little lines that are drawn over the Human Torch. Her hair appears as billowing yellow and orange fire, and her costume is essentially a one-piece yellow bathing suit which melts to flame around the edges. A great, dynamic looking design, but one that was destined not to be around very long.  You see, Frankie didn’t get to enjoy her status as a second Human Torch and almost-fifth member of the F.F. for very long. During her brief career as a superhero, Frankie seemed unnaturally addicted to her power, with an insatiable lust for adventure and a seeming willingness to break the F.F.’s “no killing our enemies” rule. Yes, bad things were brewing for poor, troubled Frankie, and it would all culminate in my personal favorite story-arc of Byrne’s run, his own “Galactus Trilogy” in issues #242-244. Galactus has once again returned to earth, in pursuit of his rebellious herald, Terrax. Over the course of these issues, Terrax is depowered by Galactus after a failed attempt to recruit the Fantastic Four into offing the big guy in order to free Terrax from his bondage. When all is said and done, Galactus needs a new herald, and our own Frankie Raye shockingly volunteers to take up the position once held by the Silver Surfer. After a quick “power-up” from Galactus resulting in a new, sleeker look, Frankie flies off into the cosmos, leaving her life on earth, and a very heartbroken Human Torch, behind forever. It’s a pretty neat little three-parter, featuring, at one point, the Fantastic Four fighting alongside Dr. Strange and several of the Avengers to battle the devourer of worlds.

You see, Frankie didn’t get to enjoy her status as a second Human Torch and almost-fifth member of the F.F. for very long. During her brief career as a superhero, Frankie seemed unnaturally addicted to her power, with an insatiable lust for adventure and a seeming willingness to break the F.F.’s “no killing our enemies” rule. Yes, bad things were brewing for poor, troubled Frankie, and it would all culminate in my personal favorite story-arc of Byrne’s run, his own “Galactus Trilogy” in issues #242-244. Galactus has once again returned to earth, in pursuit of his rebellious herald, Terrax. Over the course of these issues, Terrax is depowered by Galactus after a failed attempt to recruit the Fantastic Four into offing the big guy in order to free Terrax from his bondage. When all is said and done, Galactus needs a new herald, and our own Frankie Raye shockingly volunteers to take up the position once held by the Silver Surfer. After a quick “power-up” from Galactus resulting in a new, sleeker look, Frankie flies off into the cosmos, leaving her life on earth, and a very heartbroken Human Torch, behind forever. It’s a pretty neat little three-parter, featuring, at one point, the Fantastic Four fighting alongside Dr. Strange and several of the Avengers to battle the devourer of worlds. Following this is a weird Invisible Girl solo issue where Sue’s and Reed’s young son Franklin turns himself into an adult, a two-part story featuring the return of Dr. Doom and his restoration as Latveria’s monarch, an issue featuring the Inhumans, and finally a two-part story culminating in the extra-sized 250th issue, wherein the Fantastic Four get their asses kicked by the Superman-like Gladiator before recovering to help him defeat a quartet of Skrulls disguised as the Uncanny X-Men.

So, we’re off to a good start for quite an entertaining run of comic books. As I said, I’ve really been enjoying revisiting these issues, and have found much to appreciate. Although it’s not fashionable these days to say so, I really enjoy John Byrne’s artwork. I’ve discussed his designs of Mr. Fantastic and Frankie Raye, but all of the characters look terrific. His Thing is perfect, in both physical appearance and characterization. The dopey melodrama the character finds himself caught up in works most of the time because Ben Grimm is, at heart, a dopey, melodramatic guy. I like him.

While I certainly recommend these issues to anyone who enjoys good superhero comic books, it must also be said that they fall far short of the brilliance that was Jack Kirby’s take on these extraordinary characters he co-created with Stan Lee. Certainly, Lee’s dialogue was incredibly goofy and melodramatic, but it did have a certain flow and cadence that worked well in collaboration with Kirby’s powerful artwork. Byrne’s dialogue, by contrast, can be quite awkward, particularly when he is conveying clumsy, complex exposition through his characters, which he does often, despite the fact that he also employs copious, at times overwritten, narrative captions. While it is probably unfair to compare any artist who works on these characters (or any superhero comic book) to Jack Kirby, I’m mostly disappointed that Byrne is, at times, too reverent towards the source material. While his “back to basics” approach was probably refreshing for a lot of fans who had been subjected for years to a Fantastic Four that had become just another superhero comic book, I think it would have been nice if Byrne had brought more to the table creatively, in regards to the creation of new heroes and villains, and the exploration of new worlds and universes. Such an approach is a big part of what made Kirby’s take on the characters so great, and would have been more in keeping with the spirit of Kirby than simply utilizing the elements that had already been introduced in the series. At times, Byrne comes across here not so much as an artist with a bold new vision for the future of these characters, as he does a museum curator who is eager to show off the work of a master whose collection he has been lucky enough to have been granted association with.

While I certainly recommend these issues to anyone who enjoys good superhero comic books, it must also be said that they fall far short of the brilliance that was Jack Kirby’s take on these extraordinary characters he co-created with Stan Lee. Certainly, Lee’s dialogue was incredibly goofy and melodramatic, but it did have a certain flow and cadence that worked well in collaboration with Kirby’s powerful artwork. Byrne’s dialogue, by contrast, can be quite awkward, particularly when he is conveying clumsy, complex exposition through his characters, which he does often, despite the fact that he also employs copious, at times overwritten, narrative captions. While it is probably unfair to compare any artist who works on these characters (or any superhero comic book) to Jack Kirby, I’m mostly disappointed that Byrne is, at times, too reverent towards the source material. While his “back to basics” approach was probably refreshing for a lot of fans who had been subjected for years to a Fantastic Four that had become just another superhero comic book, I think it would have been nice if Byrne had brought more to the table creatively, in regards to the creation of new heroes and villains, and the exploration of new worlds and universes. Such an approach is a big part of what made Kirby’s take on the characters so great, and would have been more in keeping with the spirit of Kirby than simply utilizing the elements that had already been introduced in the series. At times, Byrne comes across here not so much as an artist with a bold new vision for the future of these characters, as he does a museum curator who is eager to show off the work of a master whose collection he has been lucky enough to have been granted association with. Still, if memory serves, future issues in this run will see Byrne building on the foundation he’s established here, even going so far as to replace one of the original team with another character. Also, while flaws should not be overlooked, the strength of these comics should not be understated: Byrne proves himself in these issues to be a man firmly in command of his craft, with an impressive ability to construct satisfying short adventure stories that satisfy as individual, 20-page units, but also add up to an engaging serial narrative. His character designs are first-rate, and his grasp of the characters and their personalities is very strong. Were these comics being released today, they would be amongst the best currently being offered by the superhero publishers, and if that comes across as damnation by faint praise, it was not intended as such. While these comic books may not quite deserve a place next to Kirby’s run in the canon of great superhero comics, they certainly deserve to be read and enjoyed on their own merits, and I hope that this essay has gone some small way in encouraging you to do so.

Comments